“Reversing the brain damage” to treat mental diseases

As Wang talks about the inner working of the brain, her eyes light up. “The human memory is a big mystery. The experiences and knowledge we accumulate as we age eventually shape us as individuals distinct from one another.” Her passion, or more like obsession, for the brain’s ability to memorize information and experience began in her late teens. Wang continues to push the limits in the study of life sciences because she sees vast potential for new methods of treatment that can help this generation and those to come.

iCeMS Kyoto Fellow,

Assistant Professor

Dan Ohtan Wang

Dan Ohtan Wang

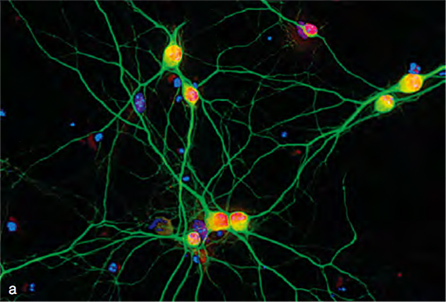

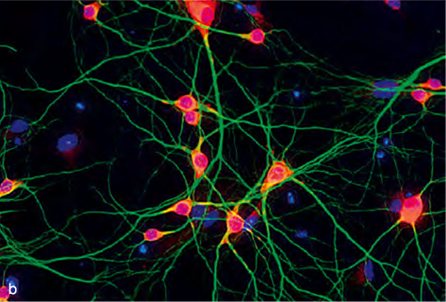

The human brain is made up of several thousand-billion brain cells, each nerve cell with an average of a few thousand synapses that form an intricate network responsible for learning and memory. Wang’s research explores how these synapses function on a molecular scale in memory formation and preservation.

Born in Shenyang City of Liaoning Province, China. After graduating high school in 1994, she entered the school of Bioscience and Biotechnology at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in Japan. In 2000, she studied Cellular Molecular Biology at the Univ. of Alabama. In 2002, she transferred to USC and received her PhD in 2004. From 2005, she worked as a postdoc at UCLA, as a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Overseas Researcher at RIKEN, and as an Asst Prof at iCeMS since 2011. In 2015, her research project was selected by the Hirose International Scholarship Foundation as the first project to be funded in neuroscience.

Dreaming of becoming a doctor

“My mother comes from a lineage of doctors. I heard that my grandfather was famous in his village for his expertise in both Western medicine and Chinese traditional and herbal medicine.” She was inspired by her family to pursue a profession where she could help people. “I enjoyed learning about biology and health in school. I thought, maybe this is the direction I should be headed...” Wang was about to enter middle school when she had the idea of studying abroad in Japan. Back then, her hometown, Liaoning Province, had close to zero foreigners. One daya gift of paper cranes was sent to her from a Japanese elementary school. “ ey were breathtakingly beautiful. I began to take an interest in Japan and had to nd out more about the country.” Around the same time, watching Japanese movies on TV became her new obsession. “‘Izu no Odoriko ( e Dancing Girl of Izu)’ was my favorite. I was a huge fan of the lead actor.” Soon she longed to visit Mt. Fuji, which appeared as a landmark in TV shows.

Six years of classes, experiments, and working part-time jobs

Wang’s rst college choice was one in Japan. She attended a language school for three years to prepare for exams but still dreamt of becominga doctor. “Back then, only Japanese nationals were eligible to attend Japanese medical schools. I had to choose between becoming a doctor in China or studying abroad, and I chose the latter.” She ultimately picked a university program that was close to medicine, the Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Science and Engineering at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. An emotional teenager traveling overseas for the rst time, “everything was so di erent from China,” says Wang. “Tokyo is a city full of exciting information and commercial goods. It’s still a special place for me.”

In her undergraduate degree, Wang studied immunology to explore the world of genomes under Prof Akira Kudo. e theme of hergraduation thesis was genomic rearrangement and the somatic hyper mutation in immune cells. e human body produces antibodies for all antigens that invade it, and this process, on a molecular level, is a rearrangement and facilitated mutationing process of the genome.

“ e genome has this incredible ability to deliberately mutate to increase variation. If we can discover how this works, we can understand how to treat particular illnesses.”

However, learning experimental techniques and conducting research was an arduous experience for her. Rent and monthly bills ate away most of her scholarship money. Lab work and part-time jobs occupied most of her free time. After nishing her master’s degree, Dr Kudo suggested studying in the United States so she could focus more on research. “Dr Kudo was extremely supportive in many aspects, not just my research but also the practical side of life.”

Visiting multiple labs in America

At age 24, Wang joined Prof PeterBarrows’ lab to make a fresh start at the University of Alabama, where she studied genome reorganization and mutation mechanisms. However, soon after her move, major discoveries in her eld were published in the journal, Cell. “I felt a sense of despair, that there was nothing left for me to do. Looking back, those two papers only revealed a small part of the immune functions. But back then, I couldn’t help but feel depressed.”

She picked herself up by building her con dence in the eld of research. “In America, where people of many cultures and races coexist, there are no given standards of how a person should be. I felt free to be who I was. I was treated the same as everyone else.” What followed numerous labvisits was her newfound curiosity toward neuroscience. “ e world we see and the world projected in the brain, are they identical? And how can two di erent people recognize the same color? I was intrigued by lectures that addressed simple but fundamental questions like this.”

Rewiring the brain’s neural circuit subconsciously through experience

Wang transferred from the University of Alabama to USC to study psychiatry, after learning that a person’s emotions or wakefulness- sleep conditions are controlled by the chemical balance in the brain. “I have been studying transporter molecules, or neurotransmitters(brain hormones) like serotonin and dopamine, since I was in graduate school. I wanted to understand the molecular mechanism of how we feel ‘happiness’ is in uenced by memory.”

Wang looked at the brain’s memory storage process, or “episodic memory”, a subconscious rewriting that occurs in the brain’s neuronal circuit every time a person experienc- es something new. is inspired her current research, which may lead to better treatments for mental diseases. “Molecular biology is my expertise... I was certain that this was the eld I could shine in.” According to Wang, by seeing and analyzing genomic activity in a living brain’s neural pathway, researchers can begin questioning where and how memoryis being stored. Discovering the function of RNA (ribonucleic acid) and unveiling memory function seem like two dots that simply do not connect. “My job is to ‘bridge’ thedivide. Understanding RNA is not a cure-all, but it can certainly help develop a hypothesis. We needed a hook, and this was it.”

Seeing the world through different colored glasses

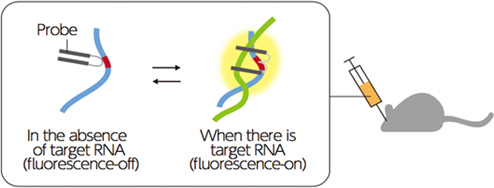

Wang returned to Japan in 2010 to join Riken at Wako, Saitama prefecture. She resided for a year at the Organic Synthetic Chemistry Lab to make probes, or “illumination markers”, that help visualize RNA activity in a living brain. When seen from a chemist’s point of view, RNA looked completely di erent. It was almost like seeing a magic trick for the rst time. “ e special probes instantly make the RNA shine when injected into the cell.” After practicing with various tools since her days in UCLA, seeds started to bear fruit in Kyoto. Approached by Dr Nakatsuji, founding director of iCeMS, at an iCeMS seminar, she soon became in charge of a research group. Japan’s strength in chemistry helped produce many groundbreaking discoveries and consequently Nobel Prize winners, and Kyoto University is one of the best universities in Japan. “I felt that my research could only be achieved in Japan. I am experiencing a life that I could never have imagined beforearriving here.”

Using the mechanism of learning and memory

e truth is, many people su er from mental illnesses in the modern age, and plenty of previous studies prove that these illnesses are related to patients’ gene abnormalities. Surprisingly, the only e ective treat- ments that exist are medication and electric shock, despite treatments for mental diseases being around for some time. Eliminating side e ects of drugs have proven di cult since it leaves the entire body vulnerable to the drug’s e ect. ere are ways to directly control the chemical balance of the brain and modify the genome, but Wang suggests we tap into our innate functions, such as memory and learning. e brain’s neural network is being constantly overwritten by external signals. By taking advantage of the brain’s “reversibility” we can ne-tune the expression pattern of the genome just by changing the surrounding environment. “If the neural network is rewritten by gene expression, behavior can be altered,” says Ohtan. Antidepressants promote the production of serotonin and help deliver them to the body. “ e human brain is not a ask. To treat the target area, it is far more e ective to use the brain’s delicate import system. Why? Because the brain has the inherent ability to restore itself.”

She is experimenting on mice for her project on targeted RNA illumination. “One day I want to develop probes that can be used in hospitals and clinics,”says Wang. “My teenage dream of becoming a doctor is connected to where I am now.” She says iCeMS has provided a perfect environment where researchers across disciplines can engage in discussions that lead to innovation. Wang’s research happens to be a concoction of life sciences and technology. “I discovered that there are no limits to fusing disciplines at iCeMS.”

Challenges of leading a team

Wang is the head of her team of ten sta , all working toward one goal: nding links between genes and brain plasticity. However, the process is a constant tug-of-war, and multiple experiments collide. Research background and interests vary from person to person, and the ideas and interpretations of results largely in uence the overall direction of the project. Small di erences can lead to interesting developments or digress from the original plan. “I struggle to find a balance between exercising the right amount of leadership and respecting the space of each sta . Needless to say, leadership is essential in order to produce maximum results from projects that are limited in time and resources. I need to communicate and manage sta e ectively. Sta members that are actually doing the experiments are one step ahead in the future by coming into contact with the latest data, and I am in the past waiting for them to report to me. I want to minimize this time lag. Until now, I was ne with having one hard drive, but I am learning to compartmentalize according to the role that I play.”

Family time is just as important

Wang steps into the o ce before nine a.m. She begins her morning routine with a cup of co ee and ipping through science magazines such as Nature, Science, Cell, and Neuron. “I enjoy this time a lot,” says Wang. After the lab members arrive, she attends meeting, checks e-mails,and nishes other administrative tasks until noon. During lunch she takes the time to interact with her lab members. “Research funding applications, writing papers, updating the group homepage... I am always writing. Around six p.m. I take o to pick up my daughter. I eat dinner with my family. We even play games together. My daughter turned nine. Iwanthertogrowupsoshecanbe my scientist buddy [laughs].” Wang’s husband is also a researcher. Same age, and at similar stages in their careers, the couple often turn to each other for support. “My little girl seems to have taken on some of our traits. One day I came into work and opened my bag. ere was a note with a message that read ‘good luck with your paper.’ Around the time of the Nobel Prize Announcement, she asked how many Nobel Prizes I’ve gotten so far. In a way, she has helped a lot; she gives me energy.”

Cooperation: Kyoto Tsushinsha Press

*This article was originally published in the newsletter “iCeMS Our World Your Future vol.1”. All the information on this page, including the researcher’s affiliation, is current at the time of publication.